Selecting a mooring bollard is often treated as a checkbox exercise in port construction projects. However, getting it wrong can lead to catastrophic failures, expensive replacements, or operational bottlenecks.

In this technical guide, I will walk you through the critical factors—capacity calculation, line angles, spacing, safety factors, and the hidden pitfalls of manufacturing quality—that every port engineer and buyer must know.

How Do You Calculate Mooring Bollard Capacity (SWL)?

The first question is always: "How strong does it need to be?"

In most cases, clients come to us with a tender document where the Safe Working Load (SWL)1 and quantity are already specified by the design institute. We strictly follow these specifications to ensure compliance.

However, for early-stage projects or consultation phases, we often support our clients in calculating the required tonnage. The calculation isn't a guess; it's physics.

We look at:

- Vessel Displacement: Heavier ships need stronger bollards.

- Windage Area2: Large container ships or cruise liners act like sails in the wind.

- Current Load: The force of water pushing against the hull.

If you are in the planning phase and need support verifying your calculations, our engineering team can assist you to ensure you aren't over-engineering (wasting money) or under-engineering (risking safety).

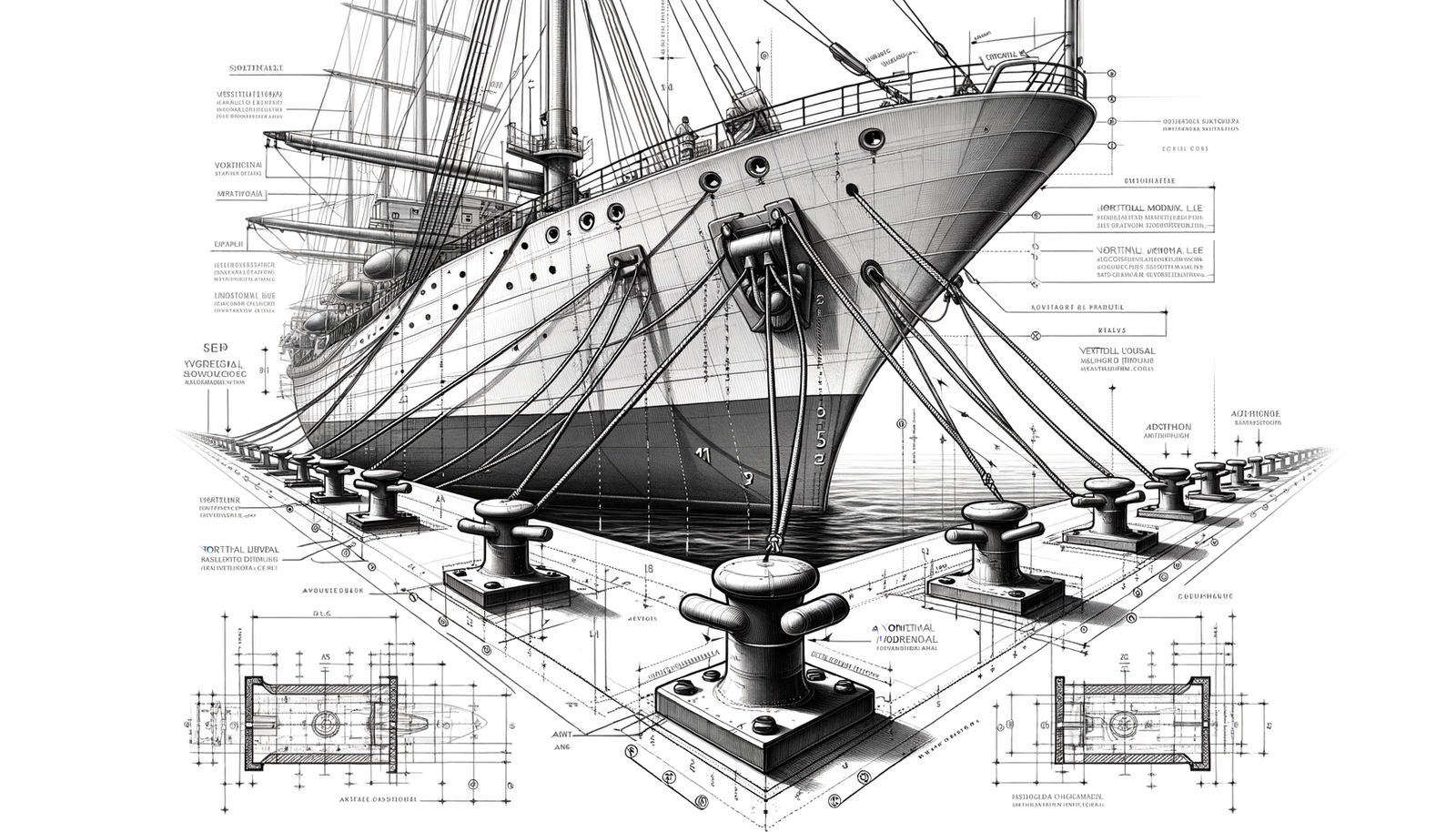

What Are the Standard Mooring Line Angles?

A bollard's capacity is meaningless if it can't handle the pull from the right direction.

Mooring lines rarely pull perfectly horizontally. You must consider:

- Vertical Angles: Depends on the tidal range and the vessel's freeboard height (empty vs. loaded).

- Horizontal Angles3: Lines can pull parallel to the berth or perpendicular to it.

Common standards (like BS 6349 or PIANC) typically require bollards to withstand full SWL within a specific range of angles. For example, a T-Head bollard is excellent for steep vertical angles, whereas a simple cleat might fail if the line pulls too high. Always check your port's extreme tidal conditions before selecting a bollard shape.

Bollard Spacing: How Far Apart Should They Be?

Spacing is about load distribution. If bollards are too far apart, you put excessive stress on individual points and lines. If they are too close, you waste budget and clutter the quayside.

General guidelines suggest spacing based on the length of the vessels (LOA) expected at the berth.

- Small vessels: 10-15 meters.

- Large commercial vessels: 20-30 meters.

The goal is to allow for a balanced mooring pattern (headlines, stern lines, breast lines, and springs) without creating awkward angles that chafe the ropes.

Safety Factors: Why Do We Need Them?

Why do we design a bollard for 150 tons if the ship only pulls 100 tons? Because the ocean is unpredictable.

For most commercial applications, a safety factor of 1.5 is the industry standard. This covers normal fluctuations in load, slight material variations, and dynamic effects from wave action.

Storm Bollards: 2.5+

However, in regions prone to hurricanes or typhoons, we use "Storm Bollards." These require a much higher safety factor, often 2.5 or more. When a storm surge hits, the forces are violent and erratic. A standard safety margin is simply not enough to prevent a breakaway, which could lead to a massive oil spill or collision.

Common Mistakes in Bollard Selection

This is the most critical section of this guide. I often see buyers focusing solely on the "price per ton" and ignoring the reality of manufacturing.

The "Weight vs. Quality" Trap

Some manufacturers produce bollards with very poor casting quality5 (porosity, inclusions). To hide this, they increase the wall thickness significantly, creating a heavy, clunky design with huge redundancy. While this might pass a load test, it's inefficient.

The real danger arises when a buyer requests a "lightweight, optimized design" (like a modern T-Head) from a manufacturer with poor casting quality. If they try to reduce the weight without high-grade casting control, the resulting bollard becomes a ticking time bomb. It looks like the drawing, but the internal structure cannot hold the load.

The "Paint Job" Deception

Surface treatment is invisible until it fails.

We often see specifications requiring ISO 12944 C5M6 (very high marine durability). Achieving this requires rigorous sandblasting (Sa 2.5)7, specific primer layers, and controlled humidity application.

Many low-cost suppliers simply brush on a basic anti-rust paint. Without strict process control or third-party inspection, they can "fish in troubled waters" (cut corners) and offer rock-bottom prices. The bollard looks shiny on delivery day, but after six months in salt spray, it will be rusting aggressively, leading to high maintenance costs.

My Advice: Don't just specify the standard; audit the process. Ensure your supplier understands the cost of quality, not just the cost of iron.

Knowing how SWL determines bollard strength helps prevent costly failures and ensures compliance with port safety standards. ↩

Exploring this helps engineers design mooring systems that withstand wind pressure on large vessels effectively. ↩

It ensures correct alignment of bollards, minimizing rope wear and improving long-term mooring efficiency. ↩

Understanding this industry standard helps you balance cost, reliability, and performance in commercial mooring setups. ↩

Learning about casting defects helps prevent structural failures and ensures manufacturers maintain high-quality production standards. ↩

Investigating this coating specification ensures bollards resist corrosion and reduce maintenance in harsh marine environments. ↩

Understanding this process helps guarantee optimal coating adhesion and durability of marine hardware like bollards. ↩